This is the third of four parts.

Part 1: Seeing Through

Part 2: Seeing Around

Part 4: Why How We See Matters

In the first part, we considered looking through or into AI. In the second, we looked at one of the possible uses of AI, to use AI to create personal tutors for every child on the planet, from a variety of angles, that is, we looked around AI. In this part, I want to look at AI even more broadly.

A question I asked in an earlier post, was whether AI, specifically Generative AI, is intrinsically good or bad. It has disturbing aspects, but not necessarily more than your wristwatch or the clock on the wall, which have done much to transform us over the past seven centuries. The pace of AI development and deployment is unlike almost anything else. That is different from how timepieces have gradually changed our identities, one tick at a time, which may make it more damaging. On a chart, even when showing only a few years, it is basically a hockey stick, but we do not know if these rates of change and adoption will last. There are a lot of people who believe they will, and many who want us to believe that whether it is true or not.

The rub is less the technology and more the goals, whether we take a short, medium, or long-term approach, we have to consider these and their consequences. Émile P. Torres, Emily, Bender, Timnit Gebru, and others have laid out the ideologies and possible consequences that surround AI. I cannot do it as well as they do, so let me go down a slightly different path.

In an earlier essay, I followed William Gibson's lead and argued that art and the military have the coolest technologies, but artists are largely rejecting GenAI, while the military (really the whole national security apparatus) is embracing it wholesale. That is slightly exaggerated but also significant. For one thing, it means that the weaponization of AI, its use for surveillance, security, policing, and control, is assured and already happening. This means that in the short term, let's say the next 5 to 10 years, there will be little interference with the AI firms, regulation, and little oversight in this country.

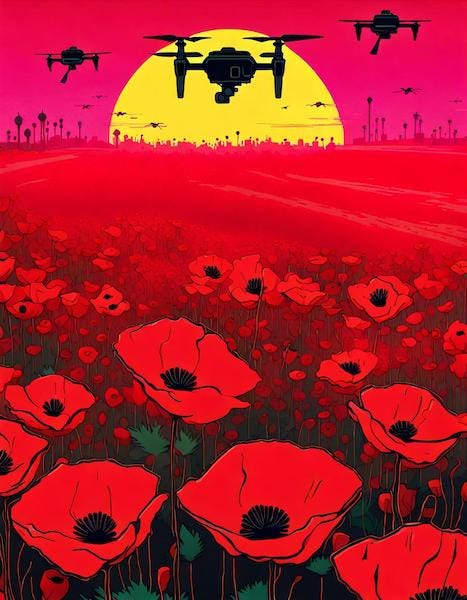

As things are developing, we may soon live in a world where "art" not produced in conjunction with AI goes unnoticed, unpublicized, and is considered quaint. The use of AI by artists, including authors, may become the de facto standard. It may be that all art and writing produced the old-fashioned way, migrates underground. The rejection of GenAI by artists and writers is understandable, it may be a mistake or it may be the saving of the arts. Honestly, we will not know for some decades. As for me, I am writing the first draft of this in blue ink with a brass-bodied ballpoint in a hard-bound notebook. As I drafted this, though, I sorted through images in my head, trying to decide if I want, and should, include an AI-generated one with this post. I did decide to go ahead and post one, but more as a demonstration of why we need artists.

In the longer term, I agree with Sarah Eaton who argues in a piece on postplagiarim that (what I call) hybrid creativity will become the norm. I do not know if that's a good thing. Likewise depending on how the technology develops, I do not know if it's a bad thing. Culturally we need to counterbalance the military/intelligence/police uses. We need the equivalent of Picasso's Guernica, or at least Rosenquist's F-111 triptych, for a generation that will grow up with AI content and perhaps AI friends.

That sounds terribly ambivalent, doesn't it? I am ambivalent about all of this. What I've learned from the history of technology is less about its inevitable success than about the complex ways it develops, its contingent pathways, the subtlety of what it does to us, and the world. Also, I have no, or no longer have, a single, well-defined ideology that guides me - just a hodgepodge of principles and contingent thoughts.

Occasionally, I come across an idea that really strikes me. Three years ago I ran across Timothy Morton's book, Hyperobjects. Hyperobjects are too large, too long in duration, and/or too complex for us to fully see or understand. I am fascinated with the idea. I am uncertain that any large language model meets all the criteria Morton sets but pretty certain that any type of AGI or ASI would.

Hyperobjects have numerous properties in common. They are viscous, which means that they "stick" to beings that are involved with them. They are nonlocal; in other words, any "local manifestation" of a hyperobject is not directly the hyperobject. They involve profoundly different temporalities than the human-scale ones we are used to. In particular, some very large hyperobjects, such as planets, have genuinely Gaussian temporality: they generate spacetime vortices, due to general relativity. Hyperobjects occupy a high-dimensional phase space that results in their being invisible to humans for stretches of time. And they exhibit their effects interobjectively; that is, they can be detected in a space that consists of interrelationships between aesthetic properties of objects. The hyperobject is not a function of our knowledge: it's hyper relative to worms, lemons, and ultraviolet rays, as well as humans.

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (University of Minnesota Presss, 2013).

Even the tools we have today definitely stick to anyone involved with them. They are persuasive, they stick to and change your work and leisure, and your data certainly sticks to them. So I think we can check off viscous.

Their manifestations are certainly non-local, no matter how good they are at conversation that you feel there's someone there talking to you, there is nothing there, just a data stream sent over networks but living in the cloud.

Skipping to interobjectivity, I think the they check that box too, as their effects, indeed they're very function, is built of probabilities of items connecting in relational spaces, and much depends on the aesthetic property of those relations.

It is the third one of Morton's aspects of which I am uncertain. How do we measure their temporality? Is it by the speed with which they analyze huge amounts of data, the time it takes them to respond, the length of time they retain data, or the supposition that ASI will lead to our permanent replacement?

Whether or not AI is a hyperobject or hyperobjects, I think it is a good metaphor. Like a hyperobject, GAI is hard to see in its entirety. We can see different aspects of it, but not the whole, not all at the same time. Like a hyperobject, we have to try to understand what it is and how it functions by making lots of smaller observations. We can arrive at a general idea, but not the details

With GenAI, we are dealing with something difficult to understand and pin down. It is never where we are, and it is potentially everywhere and nowhere. As AI agents become more sophisticated, the actual location may be spread among the many different data centers becoming ever more non-local.

That idea of interobjectivity fascinates me. I'm going to take that in a way that is probably too literal. One of the most salient points about AI is that it produces text, images, audio, and video that mimic what humans produce. To take it just in terms of text for a moment, we normally think of what it does as analyzing the statistical likelihood that, in a given context, one word will follow another one. That is dependent on a whole host of factors, but it boils down to reducing not just meaning, but also the aesthetics of a human language, to a set of statistical relationships. If it cannot arrange the words in an aesthetically pleasing order, the sentence might still be intelligible, but it will be jarring.

Take the sentence so many of us learned when learning to type on a standard QWERTY keyboard, in my case on a manual typewriter.

THE QUICK BROWN FOX JUMPS OVER THE LAZY DOG.

Now the AI might not comprehend the nature of that sentence, that the important thing is not the words, but that it contains every letter of our alphabet. So when asked to suggest some variations, it may completely ignore what is important about that sentence to an English-speaking human. This is what ChatGPT gave me when I asked for variations.

The swift auburn fox leaps over the sleepy hound.

The rapid russet fox vaults over the drowsy canine.

The nimble tawny fox bounds over the idle dog.

The brisk brown fox hops over the sluggish dog.

The speedy chestnut fox springs over the languid dog.

The agile brown fox jumps over the lazy canine.

The fast sable fox skips over the tired dog.

The spry brown fox leaps over the lethargic dog.

I repeated this with Gemini, which notices the presence of all the letters (though, curiously, only in the free version), and Claude 3.5 Sonata, which also changed the animals to other species.

Gemini:

Variations that keep all the letters:

Change the verb: "The agile brown fox leaps over the sluggish dog."

Change the subject: "A sly fox, quite brown, darts over the dozing dog."

Change the order: "Jumps the quick brown fox, over the lazy dog." (This is less common as it disrupts the natural flow of the sentence.)

Variations that don't use all the letters:

Shorter: "The swift fox outsmarts the napping dog."

More descriptive: "The cunning fox, with fur the color of rich earth, effortlessly clears the slumbering dog."

Humorous: "The caffeinated fox zips past the sleepy dog who dreams of belly rubs."

Claude 3.5 Sonata:

The agile red fox leaps over the sleepy hound.

A swift gray wolf bounds across the drowsy cat.

The nimble tan coyote hops above the idle sheep.

A speedy black panther vaults over the lethargic bear.

The fleet white rabbit dashes past the sluggish turtle.

Well, there are lots of variations here, note that none of them put the color before the adjective denoting speed or agility in English which is not acceptable. Notice also that ChatGPT does not use synonyms for "fox" but does for "dog" - possibly because the former is less common. Also note that it does not use female forms for either "fox" or "dog", perhaps because they have very specific human meanings that would have created a very different impression and aesthetic, that is it is picking up other contexts of "vixen" and "bitch". Or perhaps it is only because of their relatively low probability of use in their original meaning in American English. (I cannot recall ever hearing a native speaker of American English ever say "vixen" in reference to a fox, only to a woman, while "bitch" has become almost completely divorced from its original meaning in the US.)

I am dwelling on this aesthetic dimension for a few reasons. One is selfish, I am fascinated by the aesthetics of output, particularly in images, of these applications. A second is because, for those like me, who are not specialists in machine learning, it seems to make the mystery a little more intelligible. Perhaps it also tells us a little about why we are so ready to believe what they tell us and surrender ourselves to the illusion that there is another human intelligence there. This aesthetic aspect is important.

Finally, there is a last aspect to this metaphor. Many hyperobjects have vast gravitational fields. Metaphorically, in our culture and society, GAI, and the possibility of AGI, exert an immense gravitational field, which attracts much debate, huge amounts of our time, and gargantuan amounts of money. We have seen its ability to warp reality. We cannot do much about hyperobjects. We have to adapt to them or get out of the way. AI may not be much of a hyperobject yet, but if we let it, it may eventually become something we cannot control.

Note: Sharp readers may note in this post that I violated my injunction from the first part of the series, to avoid an analogy. That was not meant as a hard and fast rule. Sometimes we do need these analogies, and should AGI or GAI truly become a hyperobject, looking at it anagogically, as I advocated in that first part, may become vital, indeed may be the best way to see it.